Eukaryotic eDNA Baselines for CIOB Sediments and Polymetallic Nodules

Title: Deep-sea life associated with sediments and polymetallic nodules from the Central Indian Ocean Basin: Insights from 18S metabarcoding

Authors: Dineshram Ramadoss, Bharath Subramanyam Ammanabrolu, Aneesha Acharya, Jojy John, and Baban Ingole

Journal & Year: Deep-Sea Research Part II 222 (2025) 105487

BLUF: Using 18S rRNA V9 eDNA metabarcoding, this study provides an initial, conservative molecular baseline for eukaryotic communities associated with abyssal sediments and polymetallic nodules in the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB) at about 5,000 m water depth. Sequencing generated 11,078,041 paired-end reads, yielding 8,827 ASVs after denoising and quality control. Under high-confidence taxonomic assignment (0.97 threshold) plus additional filters intended to prioritize benthic plausibility, 297 ASVs remained assigned to at least the phylum level (Animalia 213, Fungi 66, Protista 18). In the assigned dataset, nodules and sediments shared only part of their ASV pool, and the IRZ station contained the largest site-unique ASV component, reinforcing the paper’s emphasis on baseline expansion for monitoring and impact assessment.

Environmental baselines are a prerequisite for credible environmental impact assessment in polymetallic nodule provinces, yet the CIOB has limited metabarcoding-based inventories relative to the Pacific. The study’s objective is to characterize and compare eukaryotic diversity associated with two substrates (sediment and nodule) across three CIOB stations representing a potential impact reference zone (IRZ), a preservation reference zone (PRZ), and an outside-area location (BC20), using a standardized metabarcoding workflow and conservative taxonomic assignment.

Sampling was conducted in June 2019 aboard RV Sindhu Sadhana using a multicorer. The paper reports station locations in both the Methods narrative and the sampling table; the sampling table provides coordinates together with depth and temperature. Using those tabulated values, stations were: IRZ at 13.562590°S, 75.562600°E (5159 m, about 1.4°C), PRZ at 12.937536°S, 74.682671°E (5063 m, about 1.4°C), and BC20 at 12.062570°S, 75.562653°E (5320 m, about 1.4°C). Sediment cores were sectioned into five 1 cm layers from 0 to 5 cm and frozen at minus 20°C. Nodules recovered from cores were brushed with sterile 1 percent phosphate-buffered saline, stored in 0.5 M EDTA, and frozen at minus 20°C for downstream processing.

A key design feature is pooling. After extraction and PCR, sediment amplicons from all five depth slices were pooled by site to produce one composite sediment library per station, and nodule amplicons were pooled by site to produce one composite nodule library per station. BC20 had no nodules, leaving five composite samples for sequencing and downstream ecological analysis: BC20Sed, IRZSed, PRZSed, IRZNod, and PRZNod. The benefits of this approach are logistical feasibility and a site-level snapshot; the cost is the loss of within-site replication and vertical resolution.

The study targeted the 18S rRNA V9 region using primers 1391f and EukBr (about 150 bp). Nodules were crushed under cold conditions, and both sediments and nodule powders were treated with EDTA prior to extraction to mitigate metal inhibition. Extractions used about 1.5 g of material with a strong chaotropic lysis buffer (including guanidinium thiocyanate and SDS) and proteinase K, incubated at 60°C for 2 hours with repeated mixing, followed by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol purification. PCR was run for 40 cycles with annealing at 46°C and included a negative control at the PCR stage; the authors note that negative controls were not included during sampling and DNA isolation. Purified amplicons were barcoded, pooled equimolarly, and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X with 150 bp paired-end reads.

Bioinformatics proceeded in QIIME2 (2023.7). Cutadapt removed primers allowing a 1 bp mismatch. DADA2 truncation lengths were 134 bp forward and 75 bp reverse, chosen based on quality (median Phred score at or above 30). Taxonomy was assigned with a scikit-learn Naive Bayes classifier at 0.97 confidence using kingdom-specific references: MZGDB (MetaZooGene Database) for Animalia and SILVA 138 for Fungi and Protista. The authors then applied a conservative, benthic-oriented filtering strategy using WoRMS and WoRDSS for marine validation, OBIS depth plausibility, and removal of phytoplankton, pelagic taxa, and taxa not previously reported from the region. This last step is important to interpret correctly: it prioritizes conservative baselining over discovery of new regional records, and therefore tends to undercount novelty by design.

Sequencing produced 11,078,041 paired-end reads; about 63 percent were retained after processing. The mean depth was 1,401,458 reads per sample, producing 8,827 ASVs after singleton removal. Under the stringent classifier threshold, only about 15 percent of ASVs could be confidently assigned, and downstream diversity analyses were restricted to the remaining assigned ASVs after the additional filters. The final high-confidence subset analyzed at phylum level contained 297 ASVs: 213 Animalia (71 percent), 66 Fungi (22 percent), and 18 Protista (6 percent). This concentration of unassigned ASVs (about 85 percent) is a central limitation and a central message, because it defines how much of abyssal eukaryotic diversity can currently be interpreted from reference databases.

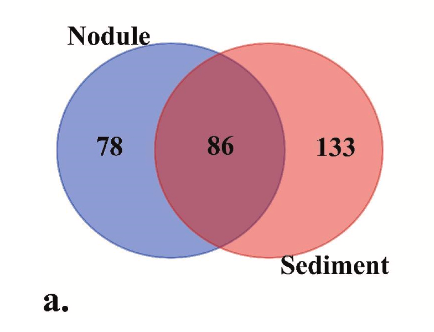

Figure 2a provides a compact summary of substrate differentiation within the analyzed subset. Of the 297 phylum-assigned ASVs, 86 were shared between nodules and sediments, 78 were unique to nodules, and 133 were unique to sediments. This supports the paper’s main ecological point that nodules, as hard substrates embedded in an abyssal soft-sediment landscape, host a partially distinct community signal rather than merely reflecting surrounding sediments.

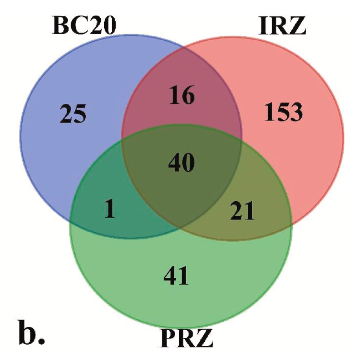

Figure 2b shows the same 297 ASVs partitioned by station: 153 ASVs were unique to IRZ, 41 were unique to PRZ, 25 were unique to BC20, and 40 were shared across all three sites.

The overlap structure in this figure is decision-relevant because it highlights how much of the assigned community signal is site-specific in this limited snapshot and why the authors call for extensive sampling to support monitoring design.

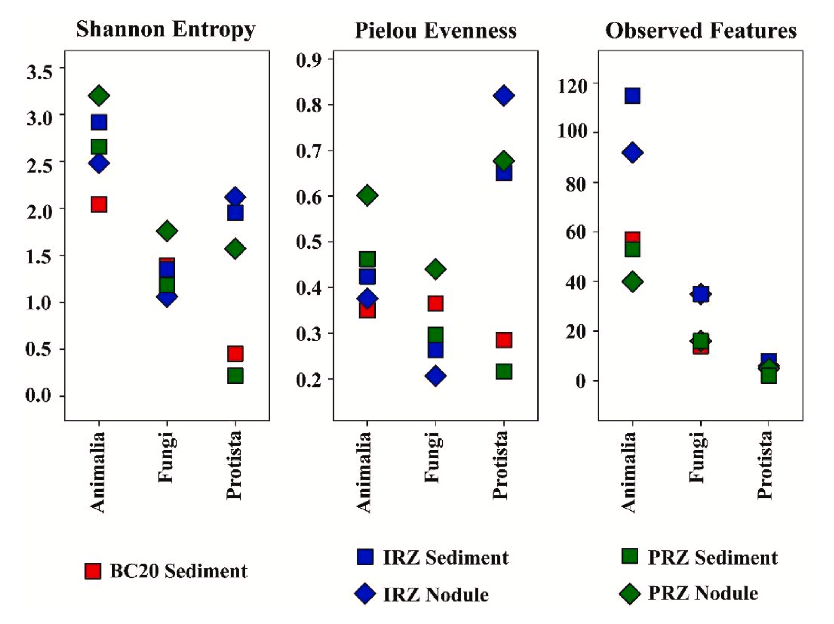

Figure 6 summarizes within-sample diversity and richness using only the ASVs assigned to at least the phylum level. In the authors’ interpretation, Shannon diversity is higher in nodule samples than sediments for metazoans, fungi, and protists, while IRZ samples contain more observed features than PRZ and BC20. Rarefaction results qualify the meaning of these differences: richness curves for sediments continued to rise even at 774,889 reads per sample, while Shannon entropy curves plateaued at the minimum post-DADA2 frequency, suggesting that sequencing depth was sufficient to stabilize diversity estimates for the assigned taxa but that added sampling could still reveal additional features, particularly in sediments.

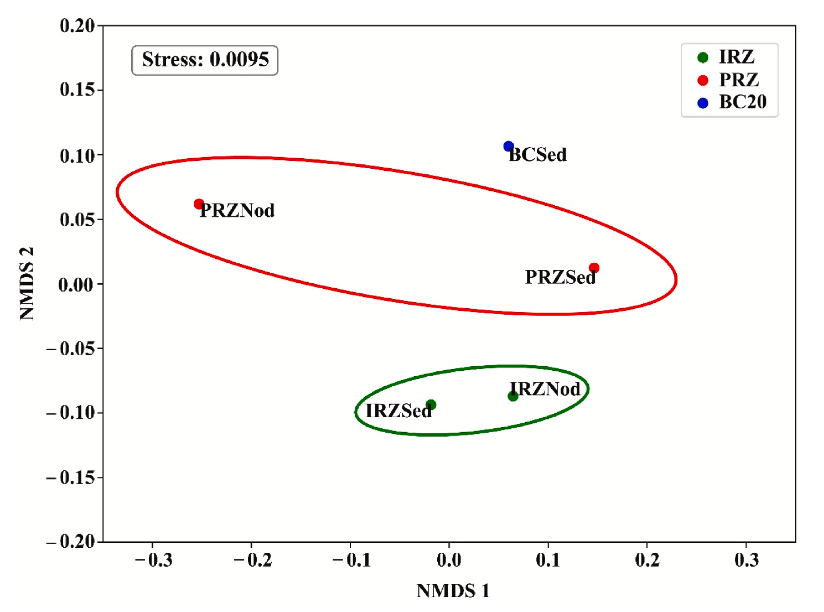

Figure 8 presents an NMDS ordination based on Bray-Curtis distances using phylum-assigned ASVs and reports a stress value of 0.0095. In this limited five-sample dataset, IRZ sediment and nodule samples plot close to each other and are separated from PRZ and BC20 sediments, with PRZ nodule composition also showing distinctness consistent with the paper’s dendrogram results. The authors interpret this as evidence that community composition differs by site and substrate, while also emphasizing that the lack of biological replication prevents inferential claims and motivates broader spatial and temporal sampling before firm generalizations are made.

Within Animalia, assigned ASVs span six phyla (Annelida, Arthropoda, Bryozoa, Chordata, Cnidaria, Mollusca) and are summarized as 29 Animalia taxa in the Results. The paper reports class-level prominence for Gymnolaemata, Malacostraca, and Copepoda and notes site-specific occurrences at family and genus levels, including several taxa only reported from IRZ sediments. Protists include Retaria as a consistent component plus additional phyla that are not uniformly present across samples. Fungi span three phyla, with Basidiomycota most abundant and Malasseziomycetes the most abundant class. The Results section reports 13 protist taxa within the filtered, assigned dataset, while the Discussion text elsewhere references 16 protist taxa; for interpretation of the core quantitative outcomes, the Results values align with the stated 18 protist ASVs used for analysis, and the internal discrepancy reinforces the need to track exactly which filters and resolution levels are being referenced when reporting taxon counts.

The study’s practical contribution is a conservative baseline for assigned eukaryotic diversity on CIOB sediments and nodules, plus a demonstration of a workflow that can be scaled as reference databases improve. For environmental assessment, two aspects stand out: nodules support distinct community signals relative to sediments within the same stations, and site-to-site differences appear substantial in the assigned dataset, which argues for baseline designs that are spatially extensive and not anchored to a single reference location.

Limitations are substantial and are clearly stated by the authors. The effective ecological sample size is five pooled composites, enabling only descriptive comparisons. Pooling of 0 to 5 cm sediment masks depth stratification, and the presence of pelagic eDNA is acknowledged as a likely contributor to the signal in upper layers, potentially complicating benthic interpretation. Controls were absent during sampling and extraction, which is important for eDNA studies; PCR negatives were used. Finally, eDNA includes DNA from living, dead, and possibly older material, so RNA-based approaches and layer-resolved sequencing are identified as next steps for distinguishing contemporary community structure from transported or legacy DNA.