Faster Autonomous Underwater Manipulation via Behavior Cloning and Speed Optimization

Title: Self-Improving Autonomous Underwater Manipulation

Author / Sponsor: Ruoshi Liu, Huy Ha, Mengxue Hou, Shuran Song, Carl Vondrick (Columbia University, Stanford University, University of Notre Dame)

Date: 2025

Report Length: 8 pages

BLUF: AquaBot demonstrates a practical route to faster underwater manipulation by combining behavior cloning from human teleoperation with an online self-learning step that tunes a low-dimensional speed scaling vector. In controlled pool experiments, the paper reports that after 120 autonomous trials, the self-optimized policy achieves a 41% speed advantage over a trained human teleoperator on an object-grasping task while also outperforming the baseline behavior-cloned policy.

The paper starts from a widely recognized gap in subsea robotics: underwater manipulation is still dominated by teleoperation because nonlinear hydrodynamics, uncertain motion, and sensing latency make precise control difficult. Operators compensate by moving slowly, especially near contact and grasp events, which improves reliability but reduces throughput. The authors frame their work as an attempt to (1) distill human strategies into a reactive policy that can run without continuous human input and (2) improve performance beyond the human baseline through autonomous trial-and-error that does not require hand modeling underwater dynamics.

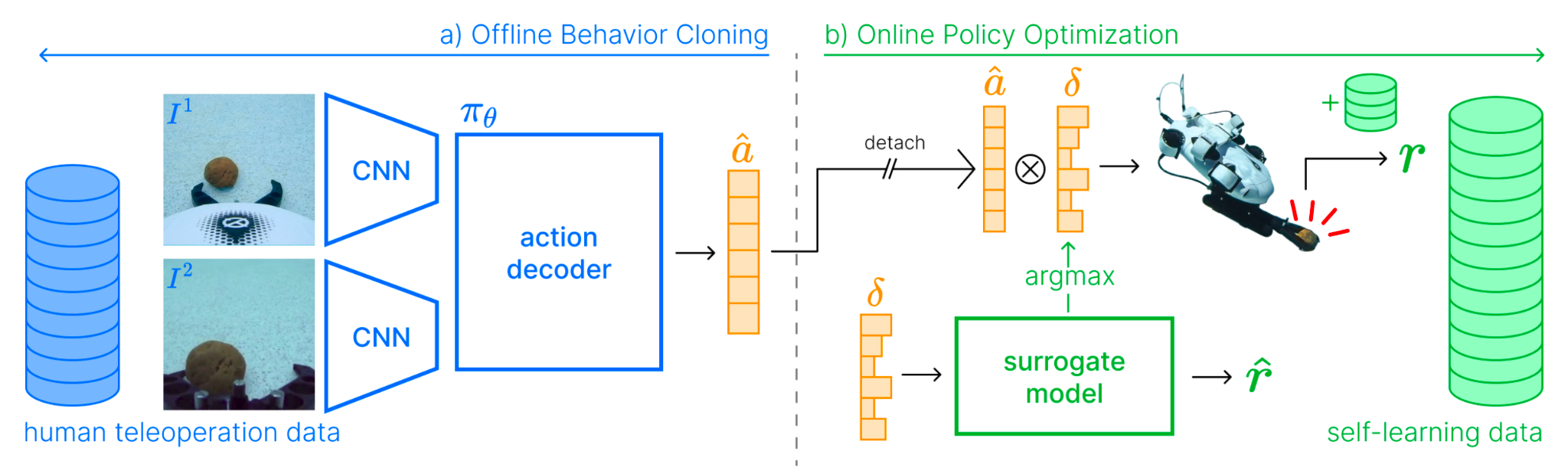

Figure 3 is the key roadmap. It shows a two-stage approach. First, AquaBot learns a closed-loop visuomotor policy from offline human teleoperation demonstrations using standard behavior cloning. Second, instead of retraining the full policy with reinforcement learning, AquaBot repeatedly runs the learned policy and optimizes only a time-invariant set of speed scaling parameters that multiply the policy’s outputs.

This design choice matters because it constrains self-learning to a small, interpretable parameter space, reducing the likelihood of unstable exploration while still capturing a major source of human underperformance: conservative speed settings during teleoperation.

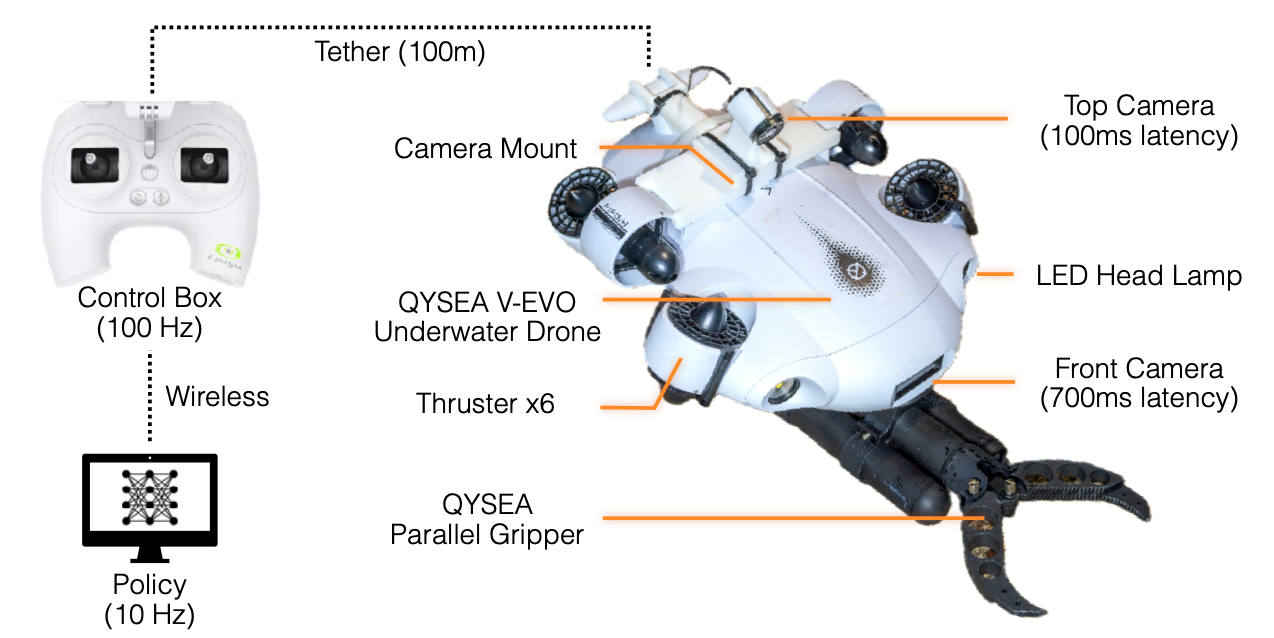

The hardware platform is deliberately low-cost and modular. The base vehicle is a QYSEA FIFISH V-EVO underwater drone with six thrusters enabling 6-DoF force and torque control and an attachable parallel gripper. The paper reports a substantial camera-latency mismatch: the stock front camera is about 700 ms latency, so the system adds a low-cost, waterproof streaming camera on top of the robot with about 100 ms latency. Control runs through a tethered box at 100 Hz. For autonomous manipulation, the learned policy runs at 10 Hz, with inference time reported well below 100 ms. In the experimental pool setup, two external cameras provide real-time localization to estimate full 6-DoF pose for navigation and for automated resetting between trials. This means the manipulation policy is autonomous end-to-end in the loop, but the experimental system still relies on external infrastructure for pose estimation and resets, and the sorting task additionally uses a PID controller for navigation and bin placement.

Demonstrations are collected by teleoperating the robot with an Xbox controller.

Visual data is recorded at 10 Hz and control data at 30 Hz. Each action is described in the paper as an 8D control vector spanning translational and rotational control plus gripper motion. The policy is trained as a force and torque controller rather than a position controller, reflecting the authors’ claim that precise underwater pose is difficult to measure and hold in their setting.

The behavior cloning policy uses two separate visual encoders, one per camera stream, each with an observation horizon of 2 frames. Inputs are resized to 224 by 224. Each encoder is a ResNet-18 with its last residual block removed and replaced by a spatial-softmax layer, producing a compact feature representation. Features from both cameras and both frames are concatenated and fed to a 3-layer MLP with LeakyReLU activations and hidden dimension 64 to predict the 8D action. Training uses mean-squared error loss for 50 epochs with batch size 32 and learning rate 1e-4. The authors also test Diffusion Policy and Action Chunking Transformers as alternative decoders and argue that longer action chunking is less effective underwater due to uncertainty, making short-horizon reactivity more valuable.

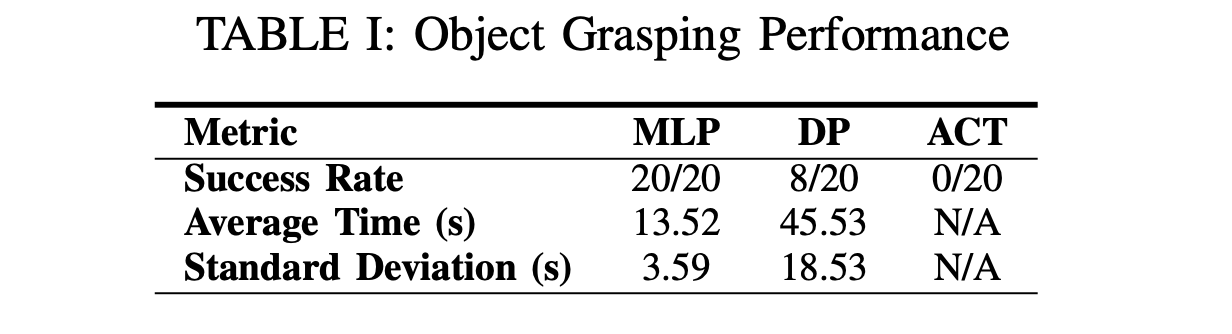

For Task 1 (object grasping), the paper collects 492 human demonstrations. Table I is the clearest snapshot of baseline capability.

The MLP policy achieves 20 successes out of 20 trials with an average completion time of 13.52 seconds (standard deviation 3.59 seconds). Diffusion Policy achieves 8 successes out of 20 with an average completion time of 45.53 seconds (standard deviation 18.53 seconds). ACT achieves 0 successes out of 20. The authors’ interpretation is that gripper timing and continuity are a dominant failure mode for diffusion and ACT under short action horizons in this underwater setting, whereas the MLP produces more reliable gripper actuation.

For Task 2 (trash sorting), the robot must grasp an object, classify it, and place it into the matching bin. The paper reports 527 demonstrations spanning three categories (toys, rocks, plastic bags), with six object instances per category. A classifier predicts object category after a successful grasp, and external-camera localization plus a PID controller handle navigation and placement. Reported grasping success rates in this sorting context are: toys, 10 out of 10 (MLP) versus 8 out of 10 (diffusion); rocks, 10 out of 10 (MLP) versus 4 out of 10 (diffusion); plastic bags, 9 out of 10 for both MLP and diffusion. The main point is that the same overall system can perform grasping and classification across varied object appearance, geometry, and material properties, while keeping the manipulation policy itself relatively simple.

For Task 3 (rescue retrieval), the robot grasps and drags a large, deformable, articulated humanoid weighing 6.8 kg, while the robot’s reported weight is 3.8 kg. The paper collects 100 demonstrations for this task and reports success rates of 5 out of 10 (MLP) and 3 out of 10 (diffusion). The authors attribute feasibility to buoyancy and underwater dynamics that allow interaction with objects that would be impractical for a similarly sized land robot.

The self-learning stage is evaluated primarily on the object-grasping task. The goal is to minimize completion time by tuning a 5D speed vector corresponding to forward/backward, pan left/right, up/down, yaw, and pitch (roll is omitted as irrelevant to grasping). The paper runs 120 fully automated episodes. Speed parameters are sampled uniformly from 0.5 to 3 during exploration. The optimization uses an epsilon-greedy loop and a learned surrogate model that maps the speed vector to predicted reward. The surrogate is a 3-layer MLP with hidden dimension 512 and scalar output, trained for 1000 iterations with batch size 8 using AdamW (learning rate 0.01, weight decay 0.1) and Huber loss. Surrogate training plus inverse optimization is reported to take under 2 seconds on an RTX A6000, so it is run before each trial.

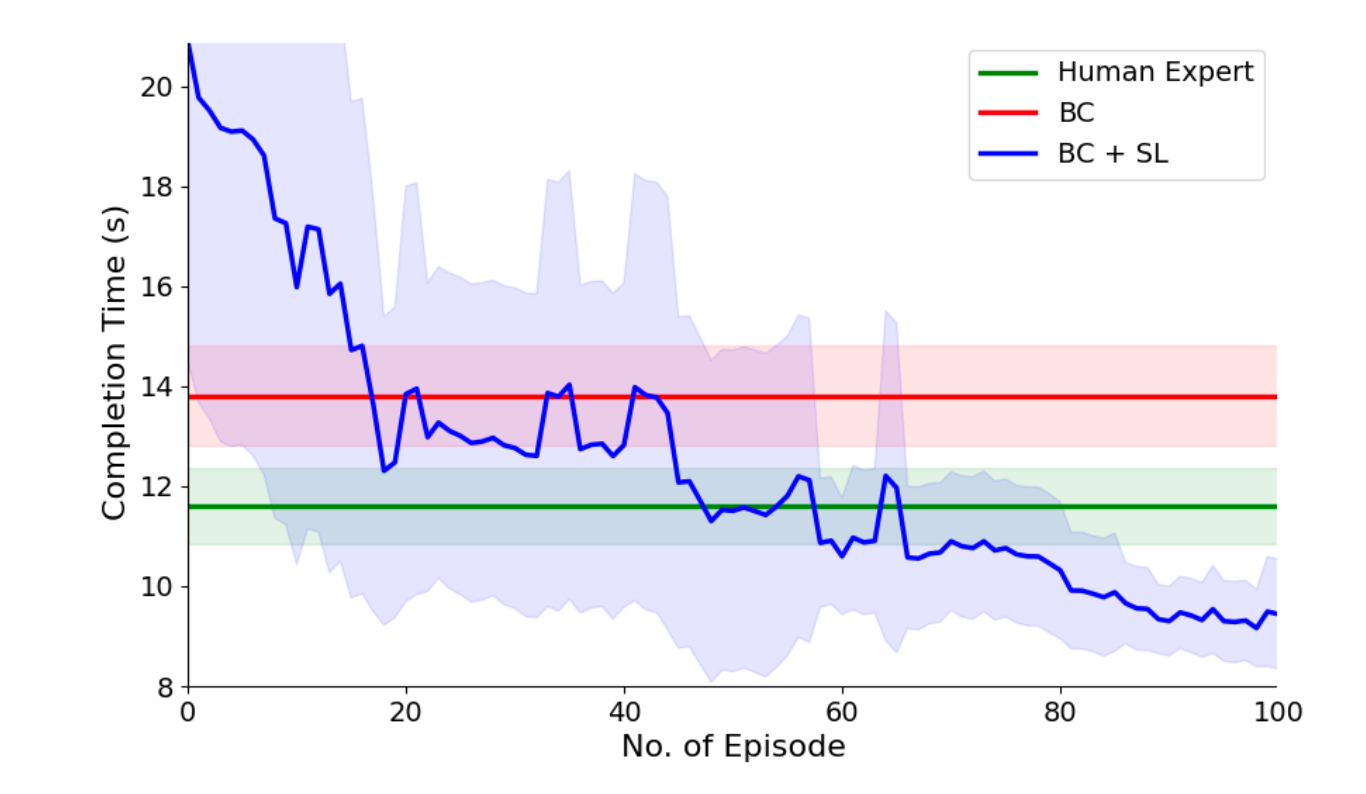

Figure 5 is the core result visualization because it shows how performance improves across episodes.

Early random speed settings often make behavior worse than both the human baseline and the base behavior-cloned policy because the robot either moves too fast and becomes unstable or too slowly and wastes time. As trials accumulate, the surrogate model identifies a speed regime that balances stability and time. The paper notes that only 100 episodes are shown in the plot because the standard deviation is computed with a moving window of 20 episodes. The headline result is that after 120 trials, the optimized policy is reported to be faster than the human baseline by 41% in speed and faster than the base behavior-cloned policy by 68% in speed for the grasping task. The paper also reports that applying the learned speed parameters to other tasks improves completion time for trash sorting and rescue retrieval by 19.6% and 22.9%, respectively, suggesting the speed tuning is not strictly task-specific.

From an applied perspective, the contribution is a pragmatic autonomy recipe that can translate to subsea industrial operations where teleoperation is expensive and operator caution limits throughput. The paper does not claim open-ocean readiness, but it does show that once a robot has a competent closed-loop policy, it can squeeze out significant efficiency gains through safe, low-dimensional real-world optimization. For deep-sea mining-adjacent workflows such as selective pickup, sorting, and tool handling, the general message is that autonomy can be improved incrementally without requiring a full dynamics model or a high-risk reinforcement learning deployment.

Limitations remain important for interpretation. The experimental environment is a controlled pool, with external cameras providing pose estimates used for navigation and automated resets, and the sorting task relies on a PID navigation controller. The self-learning mechanism only tunes time-invariant speed scalars rather than updating the policy itself, so performance is bounded by the quality of the initial behavior-cloned policy. The primary reward is completion time, so other quality metrics like contact forces, slip events, or safety margins are not deeply analyzed. Finally, the paper discusses automated success detection and notes potential loopholes, though it reports not observing adversarial behaviors in practice.