How a Collector Crawler Works

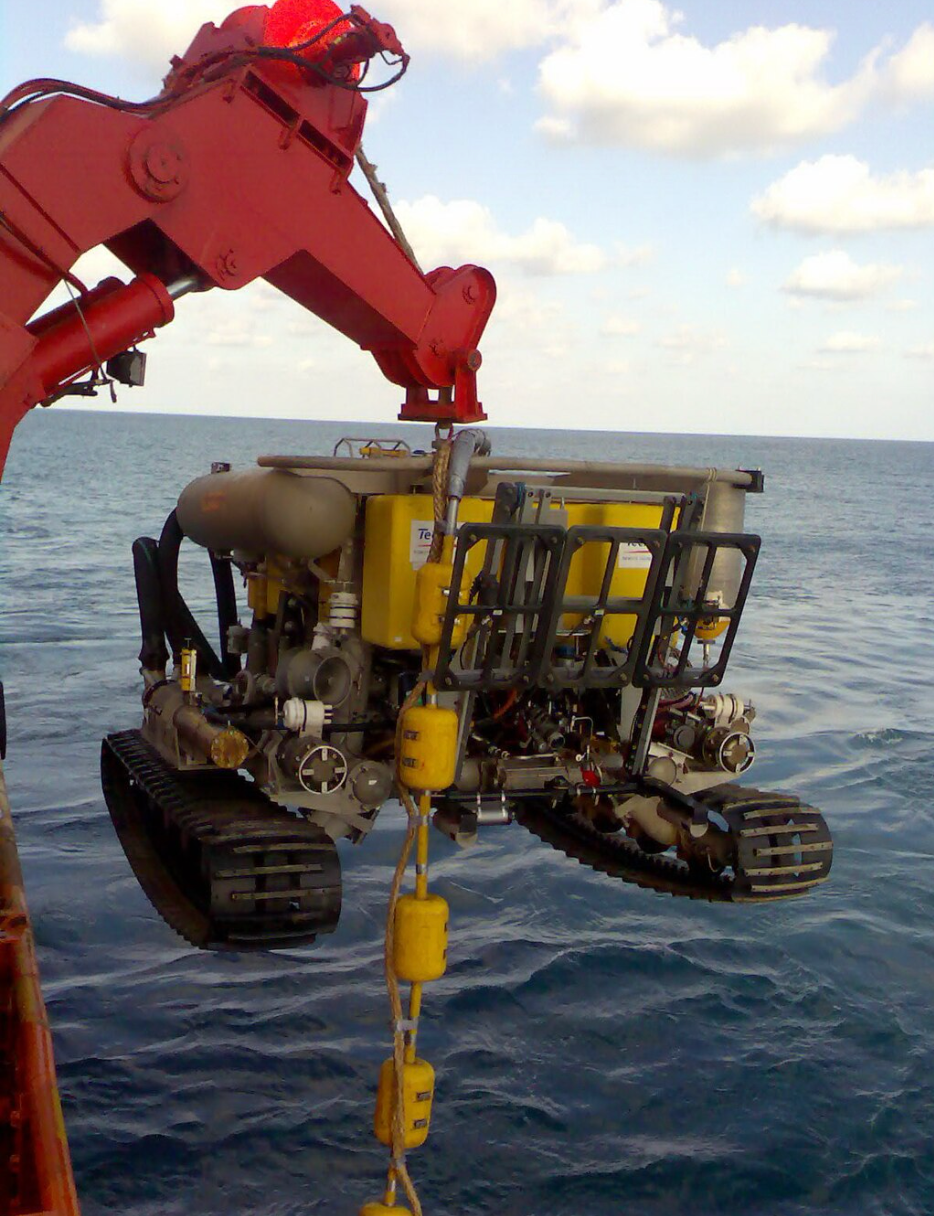

A collector crawler is like an underwater combine harvester, purpose-built for the deep ocean. Picture a flat, bus-sized robot creeping across the seafloor at walking speed, 4,000 meters under your feet.

Floodlights and high-definition cameras let operators on the ship above see what it sees in real time. Along its nose sit low-pressure water jets (or sometimes rotating brushes) that gently sweep potato-sized nodules off the mud without digging trenches.

Side skirts keep the stirred-up sediment from clouding everything, and Doppler sensors hold the crawler just a few centimeters above the ground so it doesn’t bog down or skid.

Once the nodules are nudged free, an intake mouth funnels them onto a conveyor belt inside the machine. There, the rocks mix with seawater to form a slurry that feeds the bottom of a long vertical pipe called a riser.

A powerful pump —about the size of a small car —sits just above the crawler and pushes the slurry up a four-kilometer “straw” to the production ship.

At the top, dewatering screens separate the nodules from the water; 85% of that water is filtered and sent back down another pipe to roughly 1,000 meter depth, so the surface stays clear for plankton and fish.

The entire operation is laser-mapped in advance: engineers program GPS-style tracks so the crawler covers the seabed in tidy lanes, much like mowing a lawn.

If sensors show turbidity rising too high, operators can dial back jet pressure or lift the machine for a pause.

The crawler, pump, riser and ship form a single chain — break any link and the system stops — so reliability monitoring is constant.

But when it runs smoothly, tons of battery-grade metal nodules travel from pitch-black abyss to deck, ready for the clean-energy world above.