Measuring Mining Impacts on Land and Sea with a Single Impact Wheel

Title: Comparing environmental impacts of deep‑seabed and land‑based mining: A defensible framework

Authors: A. Metaxas, C. D. Anglin, A. Cross, J. Drazen, M. Haeckel, G. Mudd, C. R. Smith, S. Smith, P. P. E. Weaver, L. Sonter, D. J. Amon, P. D. Erskine, L. A. Levin, H. Lily, A. S. Maest, N. C. Mestre, E. Ramirez‑Llodra, L. E. Sánchez, R. Sharma, A. Vanreusel, S. Wheston, V. Tunnicliffe

Journal & Year: Global Change Biology, 2024

BLUF: The paper presents the Environmental Impact Wheel, a six‑attribute, indicator‑based scoring system that enables side‑by‑side or quantitative comparison of ecosystem impacts from land‑based mining and proposed deep‑seabed mining. It specifies a five‑step workflow, uses a 1 to 5 scoring gradient tied to impact categories, and aggregates scores transparently, creating an auditable basis for decisions where data and ecosystems differ.

Comparisons between the two realms are difficult because deep‑seabed mining is in exploration with equipment tests, commercial operations have not begun, and much of the deep sea remains data‑poor. On land, mines operate across many ecotypes with different practices. Prior comparisons emphasize emissions and waste; biodiversity comparisons are mostly qualitative. The framework fills this gap by standardizing indicators, scoring, and visualization for both realms. In the CCZ, a roughly 6,000,000 km² region at 3,900 to 5,500 m depth, such standardization is necessary to interpret exploration results alongside terrestrial evidence.

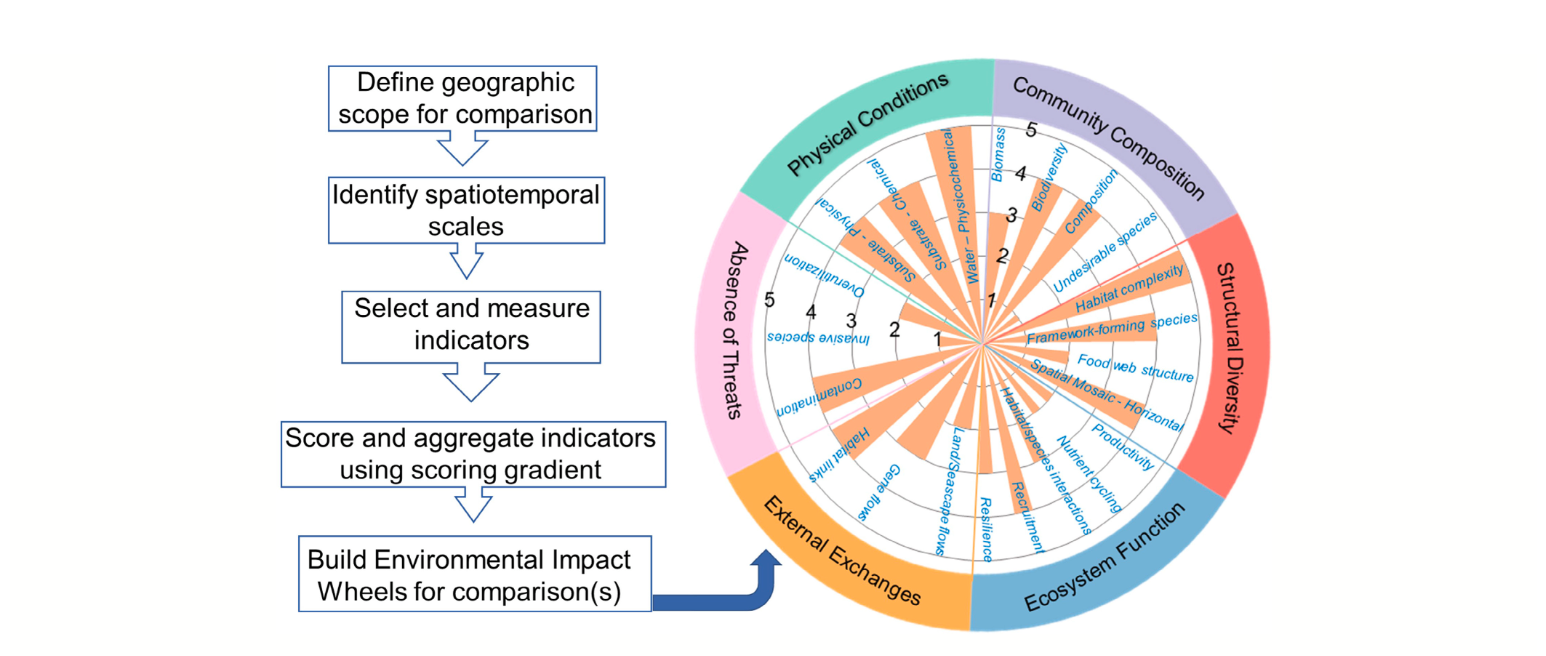

The Environmental Impact Wheel contains six attributes: physical condition, community composition, structural diversity, ecosystem function, external exchanges, and absence of threats. Each attribute includes three to five sub‑attributes scored from 1 to 5 relative to a reference site. Figure 1 lays out the five steps and shows a sample wheel for display purposes; the wheel’s numbers are illustrative rather than data and could represent either land or deep sea.

Table 1 provides worked examples of indicators for each sub-attribute, such as bulk density, particle size, permeability, and dissolved oxygen for physical condition; richness and evenness across microbes, invertebrates, and vertebrates for community composition; secondary productivity, nutrient cycling, and recruitment rates for ecosystem function; and contaminant concentrations, presence or absence of invasive species, and exceedance of allowable harvest limits for absence of threats.

Indicators measured at impacted and reference sites are mapped to a gradient of categories from negligible to severe impact. Category definitions can draw on Environmental Risk Assessments and draft ISA Standards and Guidelines. The paper gives a concrete “moderate” example that corresponds to recovery on the order of years to decades if the activity stops, the possibility of extinctions if it continues, major ecosystem change, and 60 to 90 percent of habitat affected. Numeric thresholds are established in advance, then scores are aggregated using equal weights or a weighted average I = Σ(αᵢIᵢ) / Σαᵢ that reflects indicator importance.

An explanatory box beneath Figure 1 walks through each of the five steps with short examples, beginning with how to define scope by resource and geography. Spatiotemporal scales are then selected, recognizing that effects may be localized or regional and that responses can appear immediately or after a lag, persist for years, or last centuries to millennia. Indicators are chosen based on environmental objectives and available data. Scores are assigned and aggregated with documented logic and weights. Finally, wheels are built for specific comparisons, for example changes with distance from a mining site, time since activity began or ceased, or different development scenarios, and sensitivity tests are used to explore weighting choices.

Reference sites are essential. In the deep sea, the requirement to designate Preservation Reference Zones and Impact Reference Zones within contract areas can help anchor before‑after and control‑impact comparisons if zone design follows key criteria. On land, analogous references can be harder to locate because other land uses introduce long‑running background impacts. Spatial scales may span tens of meters to hundreds of kilometers, and temporal scales from days to millennia, depending on ecosystem turnover and substrate regeneration.

The framework focuses on mining‑site environmental impacts and explicitly excludes transport, processing, and tailings disposal. Comparisons should incorporate cumulative, offsite, secondary, and cryptic impacts that are often missed by narrow project boundaries. Statistical power and detectable effect size should be set a priori for each indicator based on natural variability. The authors highlight key gaps for both realms, including sparse deep‑sea baselines, unknown non‑linear responses that may involve tipping points, and long‑term trajectories of post‑mining terrestrial restoration.

Because it turns diverse measurements into a single, auditable display, the Environmental Impact Wheel can help regulators and operators compare alternatives, set thresholds, and link approvals to monitoring. It encourages transparent weighting choices and makes it easier to align baselines with indicators that have real decision value. In areas where high‑quality reference sites can be established, the approach strengthens the scientific basis for evaluating options consistently across jurisdictions and ecosystems.