Meet the Three Ore Types: Nodules, Crusts, Sulfur Vents

When people talk about deep-sea mining, they usually mean three very different kinds of “ore” — each formed in its own underwater setting.

Polymetallic nodules

Imagine potato-shaped rocks lying loose on the ocean floor, 4,000 - 6,000 m down.

Over millions of years, metals drifting in seawater have coated tiny shells or shark teeth until each lump became a hard ball of manganese, nickel, copper and cobalt.

Because nodules sit on top of soft mud, robots can nudge them into a hopper like pebbles on a beach. Engineers like them because one rock holds several useful metals at once.

Cobalt-rich crusts

Now picture tall, extinct volcanoes that rise from the seabed like underwater mountains.

On their bare slopes, metal-rich water slowly plates the rock with a black, knobbly skin — only a few centimeters thick but loaded with cobalt, rare-earth elements and sometimes platinum.

These crusts are stuck fast, so miners can’t vacuum them up; they need cutters or water jets to slice the coating from the hard basalt underneath.

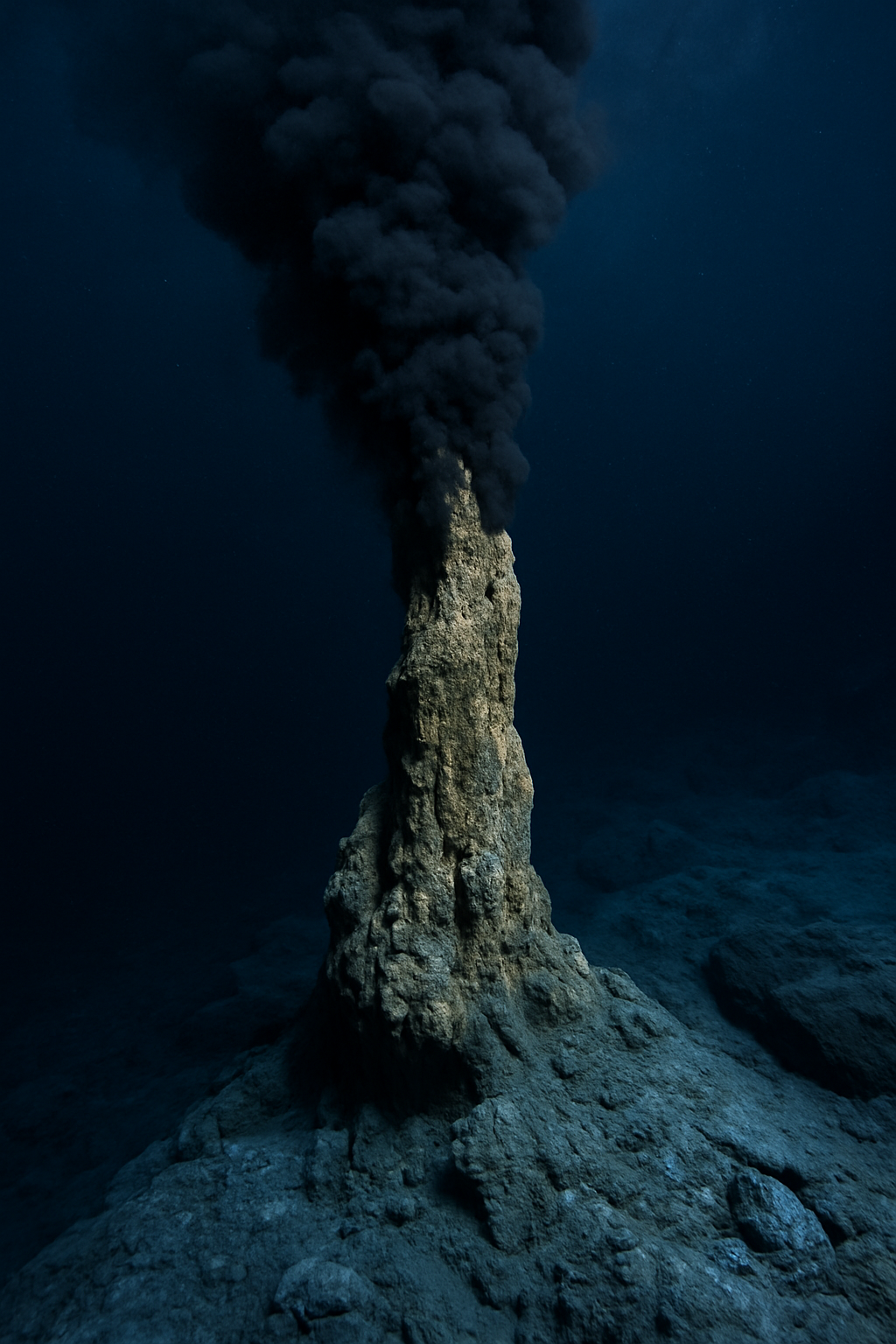

Sulphur vents (seafloor massive sulphides)

Finally, head to places where the Earth’s crust cracks open. Super-hot water blasts out, carrying dissolved copper, zinc, gold and silver.

When the fluid meets cold seawater, metals drop out and build chimney-like “black smokers.”

Over time, the chimneys crumble and pile into mounds of ore. These deposits can be richer in copper and gold than many land mines, but they sit in rugged, fragile vent fields filled with unique life that feeds on chemicals, not sunlight.

So, nodules offer an easy scoop-and-pump operation, crusts demand precision cutting on steep slopes, and sulphide vents provide high-grade metals in rough terrain.

Understanding these three ore types helps explain why deep-sea mining needs different machines, rules and environmental safeguards for each undersea neighborhood.