Sediment Plumes: What They Are and Why They Matter

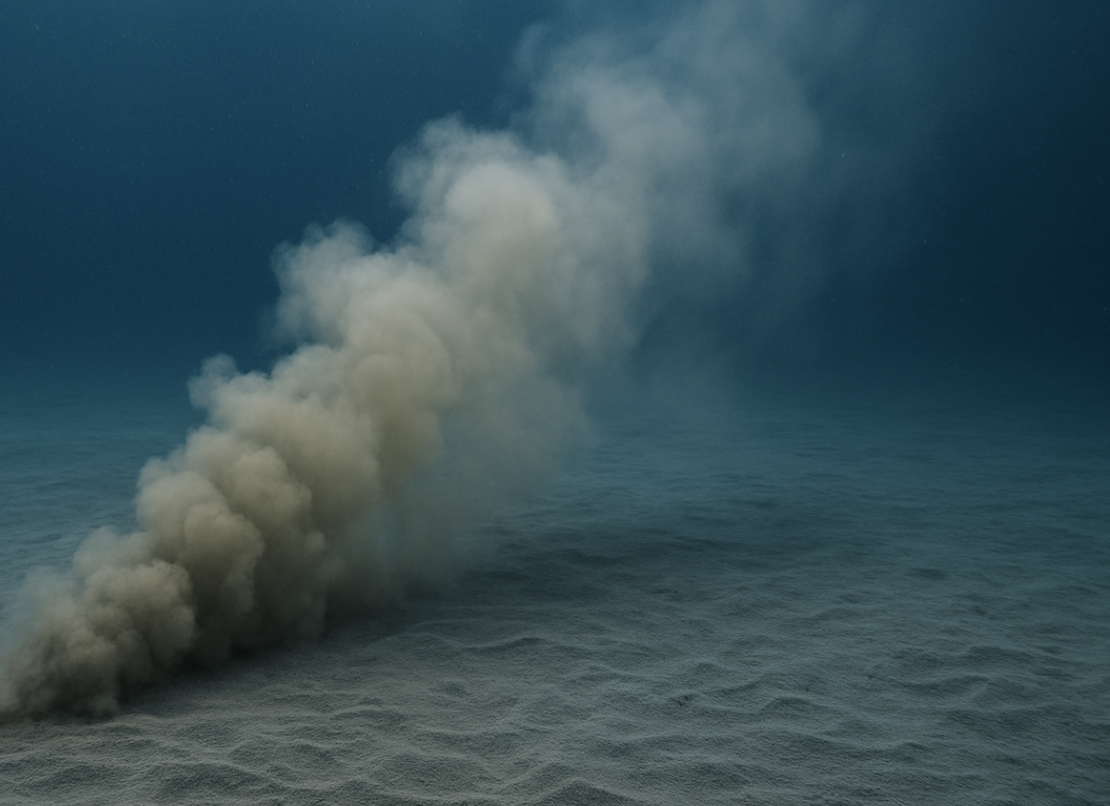

When a crawler sweeps nodules off the seafloor it doesn’t just pick up rocks — it also stirs fine clay and silt into the water. That cloud of particles is called a sediment plume.

Picture the dust trail behind a farm tractor, but underwater and moving in slow motion. Tiny grains, some thinner than a human hair, can stay suspended for hours or days before settling again, especially in the still, cold water four kilometers deep.

A second plume forms higher up when the production ship pumps cleaned water back into the ocean after dewatering the slurry. Even though the water looks clear, a small amount of ultra-fine sediment escapes the filters and exits the pipe at roughly 1,000 meters depth.

Ocean currents can carry both plumes tens of kilometers, depending on speed and direction.

Why does this matter? Many deep-sea animals — including brittle stars, sponges and single-celled foraminifera — feed or breathe by filtering water. If too much sediment coats their gills or feeding arms, they can starve or suffocate.

Plumes could also bury microscopic larvae trying to settle on the seabed, slowing the recovery of disturbed areas. Because light never reaches these depths, even a thin layer of silt may linger for decades before bottom currents sweep it away.

Regulators and scientists are therefore laser-focused on measuring plume size and spread. Contractors now fit crawlers with skirts to keep sediment low and use real-time lidar sensors to throttle pump speed if turbidity rises above agreed limits.

The International Seabed Authority is establishing rules that will set hard numerical thresholds for plume density and require companies to pause operations if they exceed them.